20 years ago Apple wasn't the global success it now is, but it had had a period of success in terms of the Mac with the almighty iMac G3 having been around for over two years and the PowerMac G4 on the shelves.

But the operating system that launched on the iMac G3 was creaking. Known as Mac OS 9, it had changed too little from the first Macintosh in 1984, truth be told. Certainly it hadn't changed a great since 1991 when System 7 was launched.

And although it was relatively simple to use, it was really a single-tasking OS in a multitasking world and looked dated compared to Windows 95 and the even better Windows 98.

20 years ago today, Apple lifted the lid on its successor to Mac OS 9. Called Mac OS X, version 10.0 onwards turned out to be a 19-year odyssey with 16 updates that became annual after a while. Big Sur, the latest iteration of macOS – as it's now styled – has finally made it to version 11.0. Like the iPhone X, the X in Mac OS X was pronounced 'ten'.

But even Big Sur was going to be the 17th version, 10.16 at one point (there were 16 versions but Cheetah was 10.0). The developer beta we tested last year was numbered 10.16 so clearly, the decision to move to version 11.0 was a late one. Indeed, Big Sur isn't that much of a step on, but it signals a new beginning for the Mac as it says goodbye to Intel power and hello to Apple Silicon.

Initially, Apple named its OS after big cats (Puma, Jaguar, Tiger and so on) before switching to Californian landmarks when the well ran dry.

Ancient origins

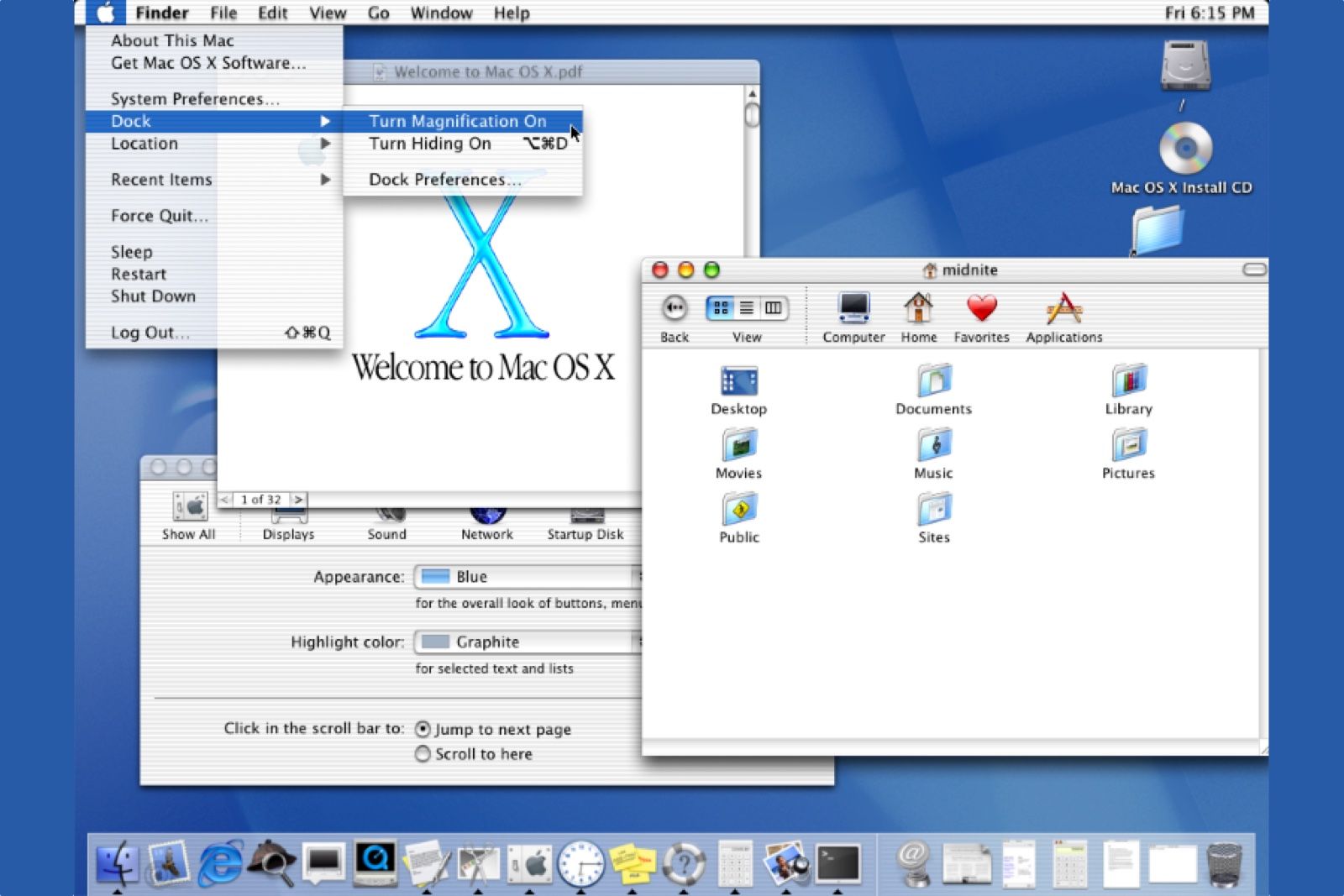

The origins of the macOS we use today are pretty ancient and actually, you can trace the lineage back to Steve Jobs' other computing company NeXT (which Apple eventually bought, heralding the return of Jobs to Apple). NeXT developed the Unix-like NeXTSTEP system which, essentially was better than anything Apple itself had tried to develop a next-generation operating system. It had something resembling the now-familiar dock, for example.

And so work on OS X progressed, with the project known as Rhapsody and the effort going into a single operating system, which was first talked about by Jobs at Macworld 2000 (see the video below). But it got delayed and it was a year before a consumer release was made.

Launched on 24 March 2001, the first version of Mac OS X Cheetah was met with a mixed reaction. It looked great thanks to Quartz graphics and a new 'aqua' interface that introduced the dock for the first time. It worked well with the internet. But it was light on features while the worst bit was that performance on PowerPC-based G3 Macs was especially poor.

App woes

You found yourself reverting to the 'classic' mode, which was essentially OS 9. Puma – launched in September 2001 – was much improved yet was still a little sluggish. OS 9 was discontinued at the end of 2001.

Many apps didn't work in OS X to begin with and various companies like Quark and Aldus didn't develop OS X apps straight away, which ironically opened the door to Adobe to eventually dominate the creative space with its Creative Suite (now Creative Cloud).

Some versions of OS X were probably worthy of being the one that became OS XI, such as Leopard which was a big update.

Regular updates to OS X didn't always solve problems. Sometimes they created them. This isn't unique to Apple of course, you'll know that Windows Me, Vista and Windows 8 didn't meet the standard of Windows XP, 7 and 10. And with OS X even 2019's final version - macOS 10.15 Catalina - was poor. It broke some apps and many were put off updating. Adobe Photoshop Elements, for example stopped working unless you had the very latest version with Adobe recommending users didn't upgrade.

Constant evolution

So why has OS X/macOS endured? Because it's been able to evolve. Someone using Cheetah could use Catalina. It's very different, but it's also the same. Looking back at older pictures of OS X, it's striking how much it has changed within the same core design – that's also the case for iOS over the last decade as well. Later versions of macOS have been more colourful which has been welcome and the design we have today reflects Apple's design choices on iOS and iPadOS as well, of course.

Big Sur is more like iPadOS than ever in terms of how it's elements are designed. That's a good thing, it's not dumbing down – coming to the Mac should be a natural step up from the iPhone and iPad. And it should be easily usable by those who've never seen it before. That's the mark of a truly great OS.