Augmented reality works best at your desktop. There’s a good reason for this. Most of the AR trickery you will have seen is where you hold up a black and white printed square marker so that your computer's webcam can see it. The software application then recognises that pattern and generates a virtual animation on your screen on top of the real world background. Hey presto, AR magic.

The trouble, of course, is that most objects and scenes out there that we would like to augmented with added information don’t have any markers on. In fact, just about none of them do. So, how are we ever going to get AR going in any useful, consumer way?

Currently, what we’re getting in mobile augmented reality apps like Layar, Wikitude, Junaio and the other usual suspects is a run around. Essentially, these apps are blind. They can’t see anything that you see through your phone’s camera. Instead, they get your locality from the GPS satellite system, which is up to 9m wrong, then the direction you’re facing according to the digital compass, gyros and accelerometers in your handset, which are not as accurate as they could be, and cross references all of that with an information database on the Internet that tells it what should be in front of you. Small wonder why it doesn’t work very well.

There is, however, an area of research called computer vision which is having a very good stab at getting over this. Georg Klein is one of the top minds in this field when it comes to augmented reality, so it didn’t take much of our grey matter to decide to give him a call over in the west coast of America where he’s traded in the life of an Oxbridge post-grad for putting his expertise to practical use for Mircosoft.

“The problems of AR are all about adding stuff to the scene if you don’t know what it is you’re going to add to,” he explains as phones ring in the background.

“There are three kinds of tracking for augmented reality.”

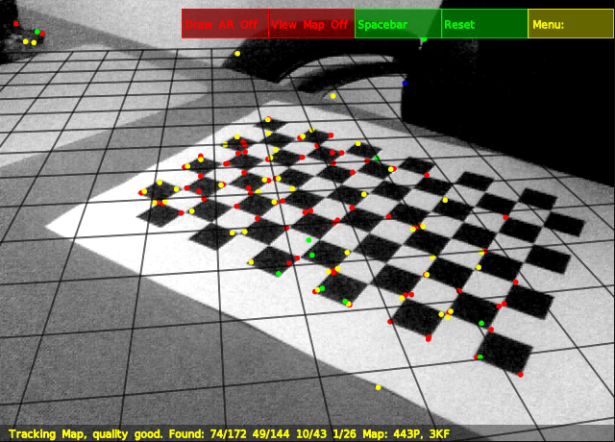

Tracking is the name given to an AR application’s attempts to recognise and follow the physical objects of a scene.

“There’s marker-based tracking which is what the likes of the ARToolKit looks for through you computer webcam. It asks for that specific shape to be recognised. It’s limited but idiot proof.

“Next is known texture or pattern recognition where the software might look for a magazine page, CD cover, Lego box, something known. It’s trained to recognise that thing very quickly. It’s used commercially but it must work on geometry that’s known in advance.

“Finally, there’s what I do but it’s quite tricky. In fact, it’s so tricky that it’s not yet at the level where anyone can really use it. I can use it. I can show people a few things and get them to use it, but it’s no good if I put the technology out there and hope for the best.”

What Georg has come up with is a camera tracking system for augmented reality which is able to model the physical shapes, lines and depth of an environment on the fly. It’s something he calls PTAM - Parallel Tracking and Mapping - and it requires no markers, no pre-maps, known templates and not even any of your mobile device’s inertial sensors either.

“It’s based on SLAM which is a system of Simultaneous Localisation and Mapping that’s huge in robotics. It’s so people’s little creations can go anywhere without getting stuck in a corner. We adapted the SLAM algorithms to work for AR.”

PTAM is freely available to download and use but, as Klein himself says, it’s not ready yet. Tracking is fundamentally and mathematically difficult. The world is three dimensional but AR only offers a flat projection of that to work with. Interestingly enough, this is why SLAM appears to work better with stereoscopic camera set ups or something like the Microsoft Kinect which has 3D depth sensor technology as well, although Klein assures us that this isn’t what he’s working on for Microsoft.

So once, the software’s been cleaned up and anyone can use it, does that mean that the issue of tracking in AR will finally have been solved? As one might expect, sadly, the answer is no, or at least not quite, anyway.

“General all singing, all dancing tracking is still a long way off. If you look at my demonstrations, yes, they look good but actually the graphics have very little to do with what’s going on in the real part of the scene. They recognise a surface and run around on it but they don’t know much about anything else or the context of that they’re doing. My little Darth Vader guy might run behind a coffee cup but he has no knowledge of what that object is or what relevance it has.

“Also, for perfect AR, it’s not enough to know where the camera is. Even if that is solved, then what about what’s around the camera?”

So, while content may still be king, it seems that context is queen and, as Klein admits, there are other systems that need to be at work alongside something like PTAM in order for the picture to be complete and for computer vision to fully understand all it sees and what is going on.

On a basic level, an object recognition technology would be a start so that mini-Darth might actually be able interact with that coffee cup by understanding what its purpose is and what it does. Of course, that would require a super-fast and reliable connection to a database of knowledge of items most likely housed on the Internet. A fully street level mapped copy of the Earth would also be a help.

As big a job as it sounds, nonetheless it’s the solution most likely, and with PTAM now re-written for the iPhone, events are well and truly underway. But, in the mean time, what AR apps does Klein himself recommend?

“Actually, I don’t really use them. I’m not that big on new technologies,” he jokes before revealing his reasons why.

“There’s a lot of current attention about gimmicky phone apps. They’re all fun and can be useful but the original intents of augmented reality were medical, maintenance, even military. They weren’t about getting your phone out to find how many stars some restaurant has got. They were useful overlays for specific tasks. Something went wrong somewhere.

“HMDs (head-mounted displays) were meant to be the evolution of AR but people have stopped working on them. Thankfully, it looks like they're coming to the idea that phone displays might not be good enough or convenient enough whereas a comfortable, lightweight, HMD could be the solution. AR might only really take off when those are developed but there’s a funding gap at the moment. None of the big companies are really investing in them.”

As Klein quite rightly points out, the companies sponsoring and setting up research centres on augmented reality are those with a vested interest in mobile, with the likes of Qualcomm and Nokia leading the pack - a good reason why the HMD has fallen by the wayside for the time being.

“AR glasses would be great and I hope they arrive. If they work properly, they seem unambiguously useful. They require the technology to be mature and flawless and there is going to be a UI problem. How do you interact with them? There’s nothing very natural at the moment.”

Some suggestions have been with added devices such as wristbands that offer haptic feedback or special gloves that the glasses can recognise but none are as seamless as people want and need such a system to be.

“Still, phones are very good so far,” Klein acknowledges, “they’’re just not as immersive."

“The thing is, you have to ask yourself with all these GPS AR apps - are they any more useful than a top down map? They’re going to get better and it’s up to the user to decide when they reach that point that they really are an improvement on the standard versions.”

For more information on what Qualcomm is doing with Augmented Reality please click: http://www.qualcomm.co.uk/products/augmented-reality